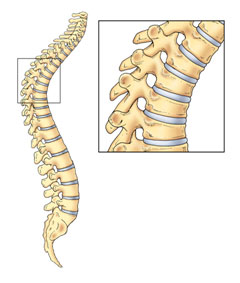

Hyperkyphosis (forward bend of the thoracic [ribbed] vertebrae beyond normal limits) is classified as either postural or structural in origin.

Postural kyphosis is flexible and will correct when the patient is asked to stand up straight. Patients with postural kyphosis have no abnormalities in their vertebrae shape.

Structural kyphosis, known as Scheuermann's kyphosis, is defined as rigid. The front sections of the vertebrae grow slower than the back sections. The abnormal kyphosis is best viewed from the side in the forward-bending position where a sharp, angular abnormal kyphosis is clearly visible.

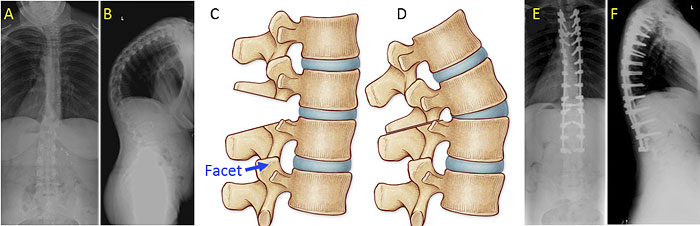

Instead of normal, rectangular vertebrae with ideal alignment, wedge-shaped vertebrae cause misalignment (Figures 1 and 2). This process occurs during a period of rapid bone growth (usually between the ages of 12 and 15 in males or a few years earlier in females). The kyphotic curve that develops with growth frequently remains mild and requires only periodic x-rays.

Patients often have poor posture and complaints of back pain, which is most common in early teenage years and less so as they approach adulthood. The pain rarely interferes with daily activity or professional careers. The kyphosis is more likely to be painful the apex (most angular section) is in the mid-to-low back instead of the upper back. In severe cases, adolescents may not be able to lie on their back without several pillows under their head.

Observation is typically recommended for:

Standing, long-cassette (scoliosis) x-rays are taken every six months as the child grows. If the child experiences pain, an exercise program is usually recommended.

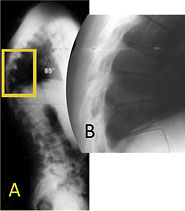

When the curve is moderately severe (60° to 80°) and the patient is still growing, brace treatment in conjunction with an exercise program may be recommended. The brace fit must be regularly evaluated and adjusted to ensure optimal correction.

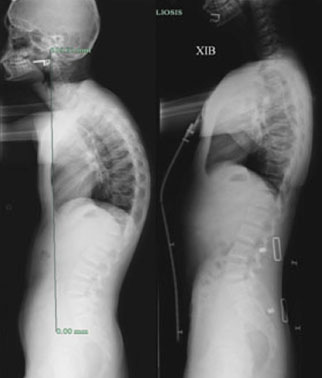

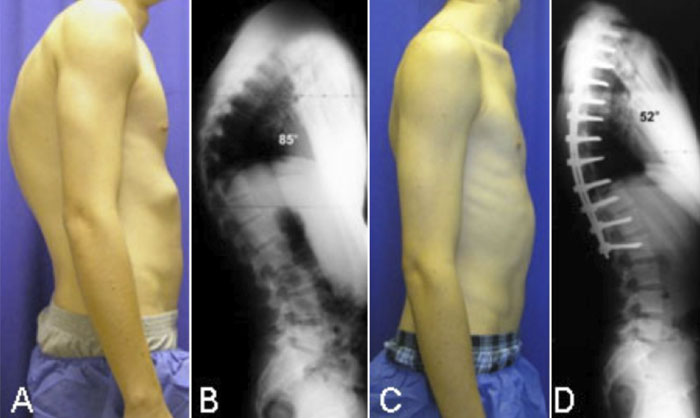

If kyphosis has become severe (greater than 80°) and causes frequent back pain, surgical treatment may be recommended. Surgery provides significant correction without the need for postoperative bracing. Pedicle screws, hooks, or sublaminar cables are placed, two per level, and connected with two rods.

Most surgeries are performed from the back; however, some physicians may recommend additional surgery on the front of the spine. Patients are usually able to return to normal daily activities within four to six months following surgery. (Figure 4).

Moderately flexible curves often straighten simply from lying face down during surgery; however, rigid curves may require additional surgical intervention, such as Smith-Peterson osteotomies.

The Smith-Peterson osteotomy involves cutting the bone to improve vertebral alignment; as a result, every spinal segment included in the osteotomy is limited in extension (backward bend) by two sliding facet joints. If these joints are removed and the disc in front is mobile, it is possible to achieve 5° to 10° additional extension, per level. (Figure 5).