Patients who have undergone spinal fusions surgery (either for scoliosis or for degenerative low back conditions) are at risk for developing post-surgical malalignment. Types of post-surgical malalignment are described below; both result in an imbalance of the spine from the side (sagittal imbalance) and lead to progressive low back pain and stiffness.

The spine is made up of individual vertebra linked together by a disc in the front and 2 small joints in the back of the spine—similar to the links in a watchband. The "links" or joints allow bending and twisting of the spine. These joints frequently become worn out, or arthritic, with aging or following injury, and eventually become painful. If pain is not controlled with physical therapy, exercise, and medication, a fusion may be suggested by your physician to stabilize the arthritic part(s) of the spine. Better methods of selecting patients for surgery, as well as better surgical techniques have made pseudoarthrosis a less common outcome of spinal fusion surgery.

Pseudoarthrosis is derived from a Greek term meaning "false joint". The term is used to describe the outcome of surgery that does not result in a solid fusion, which occurs more commonly in elderly patients, smokers, patients with medical problems, and patients on certain medications. Other conditions with an increased risk of pseudoarthrosis are:

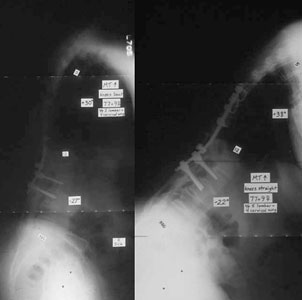

A surgeon may have difficulty determining if pseudoarthrosis is present. If pseudoarthrosis has occurred, a recurrence of pain very similar in location to that before surgery will often be noted over a period of months, or the pain may gradually increase shortly after surgery.

If a painful pseudoarthrosis is identified, your spinal surgeon will make further recommendations for additional treatment, which may include additional surgery.

Fixed sagittal imbalance (FSI) occurs when spinal alignment prevents patients' ability to stand up straight. Loss of sagittal balance causes patients to compensate by bending their hips and knees to try to maintain an upright posture. This puts greater strain on the muscles of the lower back and legs.

Distinguishing characteristics of sagittal imbalance are:

| Posture | Range | Adaptability |

|---|---|---|

| Flexible imbalance: Patients can stand up straight if they "work at it (with their hips and knees straight)" | Local: Just a few a vertebra cause significant tilt | Compensated: Patients can offset imbalance by flexing knees and hips |

| Fixed imbalance: Patients are unable to stand up straight despite best efforts | Regional: Many vertebra causing a slow forward bend | Decompensated: Patients are not able to offset imbalance via adjusted posture or stance See below. |

| Mix: Many vertebra causing a slow forward bend See below. |

When lower back and leg muscles take on the burden of compensating for the sagittal imbalance, several symptoms may result:

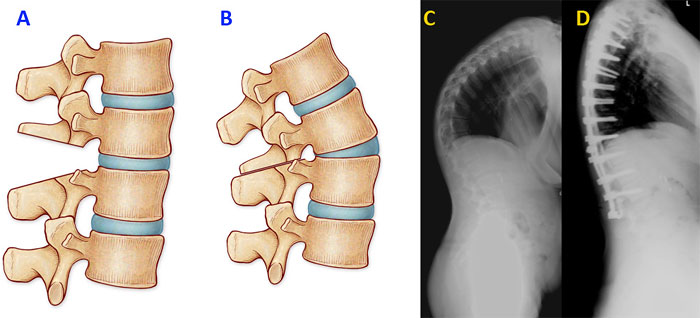

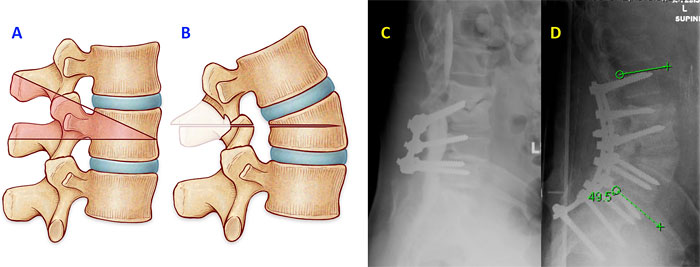

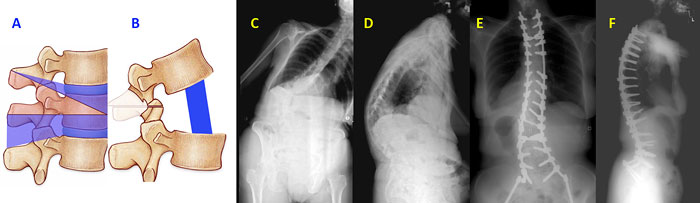

Imaging helps to assess segmental alignment, curvatures, instability, neurologic issues, and more:

Non-invasive, non-surgical therapies are typically the first recommendations for the treatment of sagittal imbalance:

Bracing is ineffective for sagittal imbalance because it weakens the posture muscles, and does not treat the underlying pathology. If the imbalance progresses and there is significant pain, surgery is usually indicated.

The decision process for surgery depends on: the type of sagittal imbalance, a history of prior surgeries, the degree and location of neural compression, the age and health of the patient, and more.

This procedure involves removing facet joints and certain ligaments. The facet joints typically limit extension of the spine so their removal (posteriorly) allows the surgeon to accentuate lordosis by tilting the bones through a mobile disc space. Over multiple levels, 5o to 15o of lordosis per level is possible.

Surgeons use this procedure to cut through segments of the spine causing sagittal imbalance. Known as a "closing wedge osteotomy", a triangle of bone is removed so the bone can be angled backwards. (The technique similar to placing a wedge between bricks, creating a sudden backward bend in the spine.) The procedure is particularly powerful, especially in the lumbar spine where the bones are bigger, and small corrections can lead to large improvements in posture. The surgery requires the support of instrumentation above and below the osteotomy and is a major surgery with relatively high rates of complications.

The most powerful (and invasive) of all spinal osteotomies, the vertebral column resection is necessary when there is a sharp, severe bend in a small area. It involves essentially dislocating the spine in a controlled manner and realigning it in the proper direction.

Like the vertebral column resection the anterior-posterior also, in essence, the anterior-posterior osteotomy (APO) dislocates the spine so that it can be repositioned properly. In an APO, he back section of the bone is removed from the back of the spine, and the front portion is removed from a separate anterior incision. The anterior-posterior osteotomy has the same effect as a vertebral column resection, but it avoids risky surgical navigating around the nerves to remove the vertebra.